“So, I ask here, What’s next for our country, For the world? The same old questions and the same old answers? No! That just won’t do! A twenty-first century Citizenship Education Program approach, combining lessens from the historic movement with modern technology and new ways of seeing and understanding our problems and challenges, just might be the answer…”

Dorothy Cotton

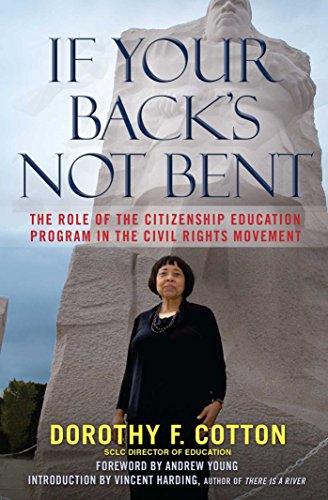

If Your Back’s Not Bent: The Role of the Citizenship

Education Program in the Civil Rights Movement

The current coronavirus global pandemic as well as global unrest ignited by George Floyd’s murder has produced a new focus on questions of justice, institutional accountability, and the need for systemic change. These days have caused me to reflect on the role Dorothy Cotton played in shaping the Civic Organizing-MACI Model.

Dorothy Cotton was the Director of Education for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) during the Civil Rights Movement. She was the only woman on the SCLC executive team and worked alongside Martin Luther King, Andrew Young, Septima Clark, and other civil rights leaders in establishing the Citizenship Education Program (CEP) located at the Dorchester Center in McIntosh, Georgia. The CEP program became the SCLC leadership development and organizing arm for SCLC. It was a primary inspiration for civic organizing agencies permanently embedded within institutions being the means for sustaining democracy as a just system of governance. Civic organizing agencies are the “21st-century active citizenship schools”.

I was in the audience in 1993, when Dorothy was describing how leaders were recruited to the 1960’s Citizenship Education Program. They were individuals playing a leadership role in fighting inequity and brutality in their community. The curriculum was interactive, expertise was in service to capacity building, and methodology was based upon open-ended questions that linked the particular experiences brought by participants to the role of citizenship: What does it mean to function as a citizen in these times? Do citizens in fact have real power? What is this power? Can they know this power? How do we work together in this decade of unavoidable diversity? What is the role of government; indeed, what is government? What is the role of the citizen? Do citizens have real governing responsibilities?

In the 5 day training, individuals developed a new sense of power and role as it related to their challenges, strategies were developed, barriers to voting were addressed including teaching people how to write cursive and to read passages from the constitution, and participants left with a plan to take on the particular problem in their community, as well as a plan for organizing community voter registration and marches. Most importantly, participants were expected to, and did, recruit other leaders from their community to attend the next monthly session, building a local base of civic leadership to support change.

I knew the story of the citizenship schools and its role in the Civil Rights Movement had not been recorded and Civic Organizing Inc. played an instrumental role in supporting Dorothy to write her book. I encourage people to read If Your Back’s Not Bent for details of this amazing effort in citizenship education tied to organizing and political transformation.

Dorothy worked with Tony Massengale, me, and others who founded Civic Organizing Inc. until she died in 2018 as we took up the challenge to reconceptualize the relationship between active citizenship-organizing-civic leadership development in 21st-century conditions.

Our partnership was productive, contentious, and authentic as together we struggled to identify what was the same and what was different from the 60’s movement politics and civic organizing. The passion movement politics invokes is something we wanted to tap into, but we wanted the passion to be enduring and in service to building democratic institutions. This was a different kind of political experience. Dorothy describes her experience: “We didn’t really know where our intense work would lead, yet we were energized, committed, focused, and determined, and held on to our goal of building a new and different America….”.(pg. 109) “We had a fire in our souls and just had to do what we did. I know now that when I took other jobs, I was just taking a break from what I was called to do. I was transformed by involvement in a people changing, country changing experience. “(pg. 283)

In contrast, civic organizing was developed as a “model” not a movement because we were conceptualizing an organizing approach that produced justice as life work carried out and fitting into all of the roles we have in families, faith, communities, workplaces, learning, and governance. We wanted to support those institutional leaders who were seeking to produce greater public accountability and effectiveness within their system by understanding the power dynamics of their institutional environments and how that dynamic was a political experience. We wanted them to identify the drive for institutional accountability with the language of democracy and justice—and the role of citizenship developed within all their institutions in which they had a stake.

That meant civic organizing had to be done within the way institutions work including the way individuals develop their sense of standing and value within the larger culture. This was a new kind of civic imagination requiring a new kind of political capacity and, because it was new, we needed to make a case for its value. The case had to be made to governing members of the institutions in which we tested civic organizing and who we needed to leverage the resources to make the case, with full disclosure that the experience would challenge the traditional and hierarchical way institutional governance was structured.

Borrowing from the Civil Rights Movement, we defined active citizenship as the inclusive role that provides rights but comes with an obligation to govern for the common good in all of our roles. We applied that idea to the challenge of organizing a broadened sense of a civic infrastructure-more than government and inclusive of all individuals and systems. A civic infrastructure that produces active citizens who hold themselves and their institutions accountable through governing policies and practices that intentionally produce justice within daily life.

We knew there were barriers within institutional culture not only to the language of politics and organizing but to the language of citizenship itself and especially citizenship as the basis for governance. Citizenship was a role one performed on their off hours—voting, volunteering, or as staff members of particular types of political organizations—advocating, protesting, or resisting. It was related to the ability to access and consume services. It was not a role identified with the need to produce and sustain democratic institutions.

Leaders who were good volunteers and held key positions within their communities were affronted at the idea of a new approach to citizenship as if they were not good enough. But the biggest challenge was that organizing within systems meant that active citizenship as an identity competed with the professional or technical identity and governing roles that institutional leaders saw as having greater status and power than that of citizenship.

We could see the need and challenge to organize a new civic imagination, a new civic infrastructure grounded in the role of citizenship as the basis for governance in a democracy. However, a key challenge to meeting that need meant that the very people who were being organized as agents for change were also part of the problem and therefore needed to change and transform themselves in the process of transforming their institution.

Though there are differences between Dorothy’s experience and leadership in the Civil Rights Movement, and today’s need to renew the promise of democracy, the development of the civic organizing agency as the primary structure for civic leadership development—leaders who organize a civic infrastructure, teach from their practice, and establish policies to support institutional members to be active citizens of their institution was borrowed directly from the Citizenship Education Program.

All of us who continue to develop civic organizing need to remember that the idea is grounded in the American experience, and the names of Tony Massengale and Dorothy Cotton are an essential part of our legacy.

This book was so good, and such a good road map for these times.